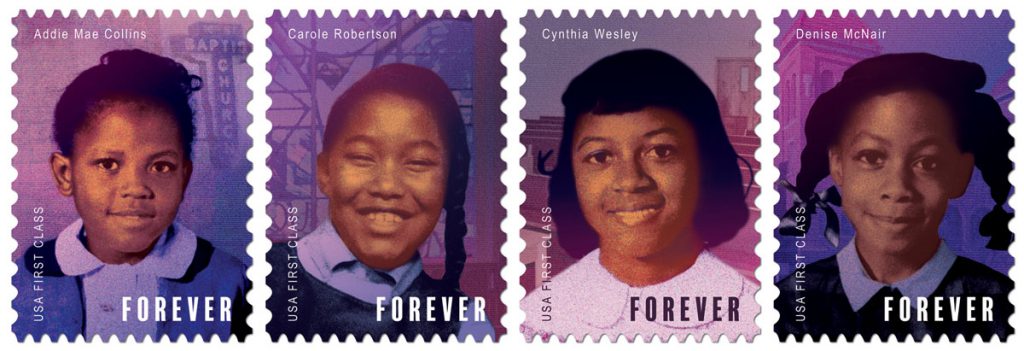

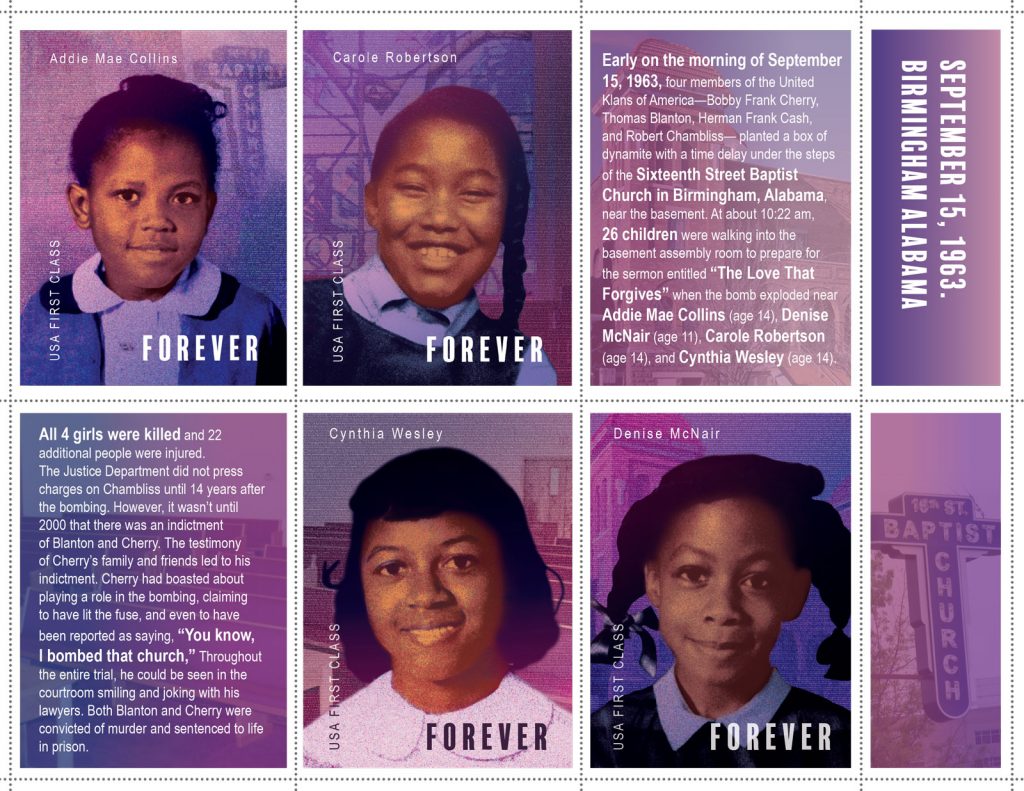

SEPTEMBER 15, 1963. BIRMINGHAM ALABAMA

Fujicolor Crystal Archive emulsion sealed between solid recycled aluminum and a high-gloss UV protective laminate.

Quadriptych, 40 x 30 inches each panel

Early on the morning of September 15, 1963, four members of the United Klans of America—Bobby Frank Cherry, Thomas Blanton, Herman Frank Cash, and Robert Chambliss— planted a box of dynamite with a time delay under the steps of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, near the basement. At about 10:22am, 26 children were walking into the basement assembly room to prepare for the sermon entitled “The Love That Forgives” when the bomb exploded near Addie Mae Collins (age 14), Denise McNair (age 11), Carole Robertson (age 14), and Cynthia Wesley (age 14). All 4 girls were killed and 22 additional people were injured. The Justice Department did not press charges on Chambliss until 14 years after the bombing. However, it wasn’t until 2000 that there was an indictment of Blanton and Cherry. The testimony of Cherry’s family and friends led to his indictment. Cherry had boasted about playing a role in the bombing, claiming to have lit the fuse, and even to have been reported as saying, “You know, I bombed that church.” Throughout the trial, he could be seen in the courtroom smiling and joking with his lawyers. Both Blanton and Cherry were convicted of murder and sentenced to life in prison.

The commemorative stamps from the post office represent a view of history that only tells part of the story.

This exhibit asks: what if the rest of the story were present and made into stamps, as well? The show Forever acknowledges civil rights martyrs that have not, and will probably never appear on the US Postage Stamps; not just the well-known supported and acknowledged civil rights leaders, for instance, but the legions of people who were unwilling participants, victims of racially motivated violence. In this way, the show also points to the false narrative that controls who we remember, how we remember them, and for how long.

Forever brings into question who makes the criteria—whether for being an official civil rights martyr, or chosen for a commemorative stamp—and what if our criteria had a different objective? What if our criteria were an acknowledgment that aimed not just at putting the past behind us, but taking responsibility for it. Restoring to view what is often pushed away, and making something whole from both our owned, and unowned, experiences.

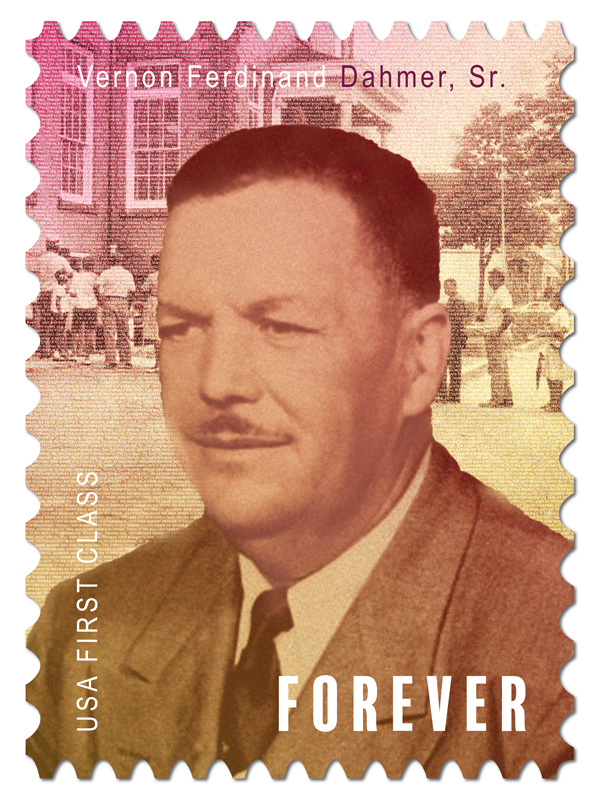

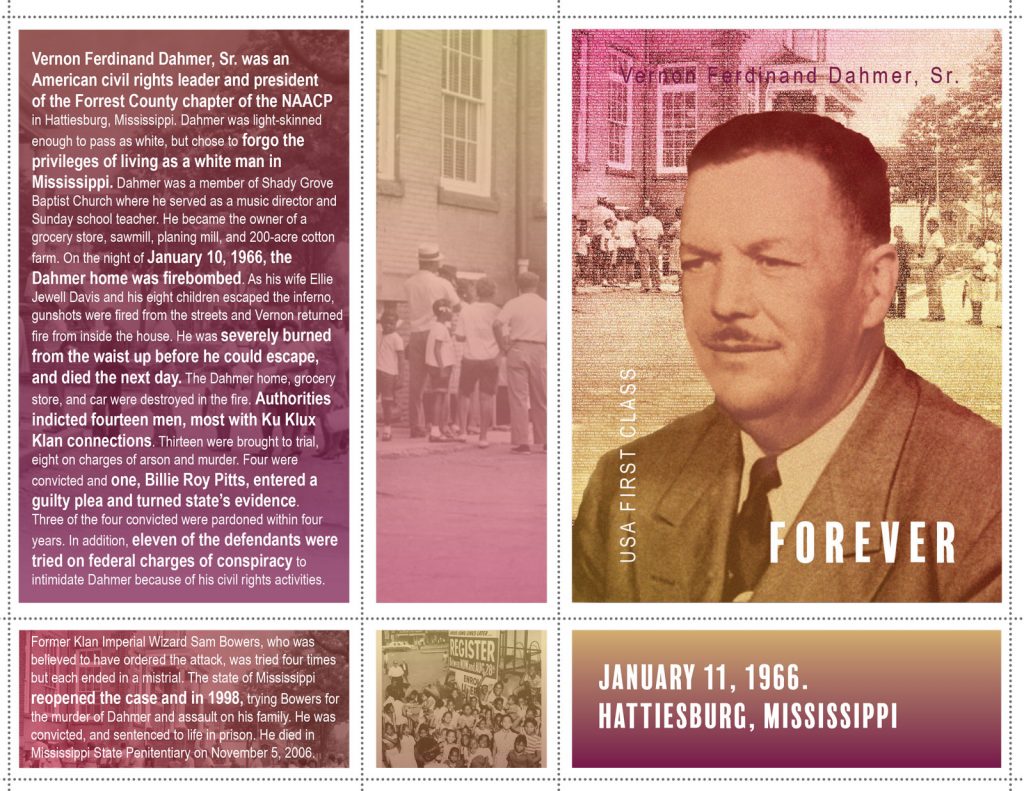

JANUARY 11, 1966. HATTIESBURG, MISSISSIPPI

Vernon Ferdinand Dahmer, Sr. was an American civil rights leader and president of the Forrest County chapter of the NAACP in Hattiesburg, Mississippi. Dahmer was light-skinned enough to pass as white, but chose to forgo the privileges of living as a white man in Mississippi. Dahmer was a member of Shady Grove Baptist Church where he served as a music director and Sunday school teacher. He became the owner of a grocery store, sawmill, planing mill, and 200-acre cotton farm. On the night of January 10, 1966, the Dahmer home was firebombed. As his wifeEllie Jewell Davis and his eight children escaped the inferno, gunshots were fired from the streets and Vernon returned fire from inside the house. He was severely burned from the waist up before he could escape, and died the next day. The Dahmer home, grocery store, and car were destroyed in the fire. Authorities indicted fourteen men, most with Ku Klux Klan connections. Thirteen were brought to trial, eight on charges of arson and murder. Four were convicted and one, Billie Roy Pitts, entered a guilty plea and turned state’s evidence. Three of the four convicted were pardoned within four years. In addition, eleven of the defendants were tried on federal charges of conspiracy to intimidate Dahmer because of his civil rights activities. Former Klan Imperial Wizard Sam Bowers, who was believed to have ordered the attack, was tried four times but each ended in a mistrial. The state of Mississippi reopened the case and in 1998, trying Bowers for the murder of Dahmer and assault on his family. He was convicted, and sentenced to life in prison. He died in Mississippi State Penitentiary on November 5, 2006.

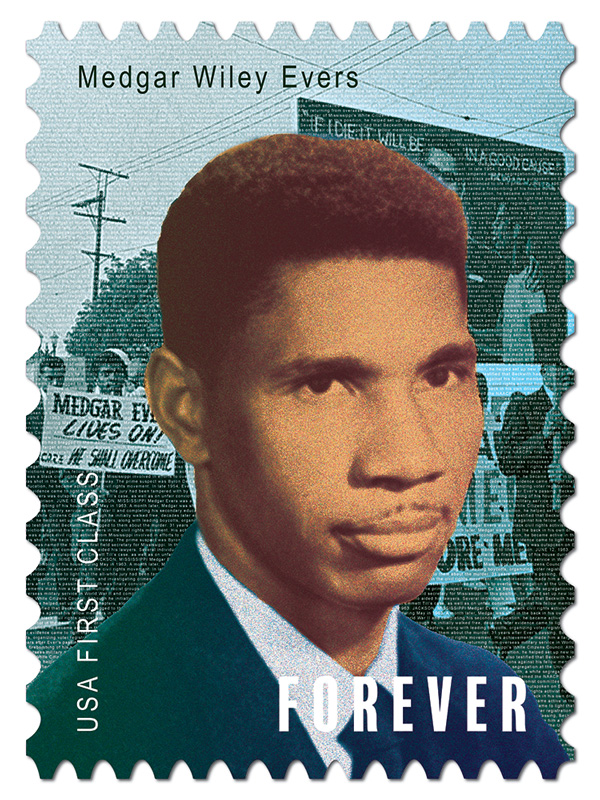

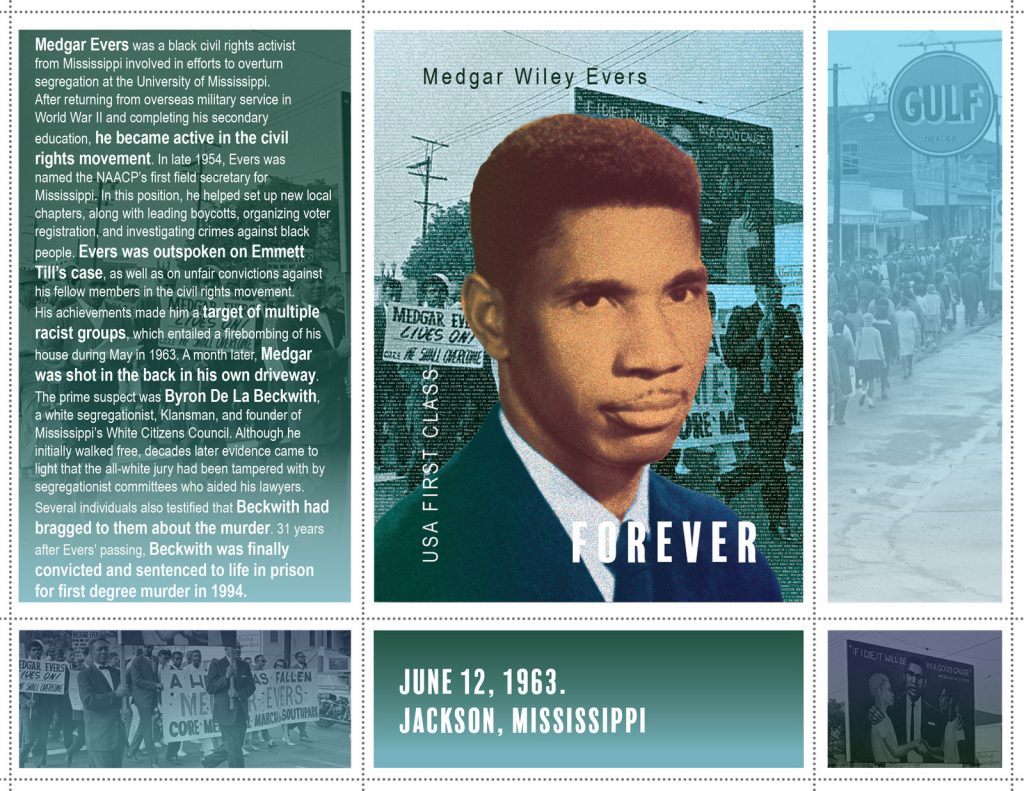

JUNE 12, 1963. JACKSON, MISSISSIPPI

Medgar Evers was a black civil rights activist from Mississippi involved in efforts to overturn segregation at the University of Mississippi. After returning from overseas military service in World War II and completing his secondary education, he became active in the civil rights movement. In late 1954, Evers was named the NAACP’s first field secretary for Mississippi. In this position, he helped set up new local chapters, along with leading boycotts, organizing voter registration, and investigating crimes against black people. Evers was outspoken on Emmett Till’s case, as well as on unfair convictions against his fellow members in the civil rights movement. His achievements made him a target of multiple racist groups, which entailed a firebombing of his house during May in 1963. A month later, Medgar was shot in the back in his own driveway. The prime suspect was Byron De La Beckwith, a white segregationist, Klansman, and founder of Mississippi’s White Citizens Council. Although he initially walked free, decades later evidence came to light that the all-white jury had been tampered with by segregationist committees who aided his lawyers. Several individuals also testified that Beckwith had bragged to them about the murder. 31 years after Ever’s passing, Beckwith was finally convicted and sentenced to life in prison for first degree murder in 1994.

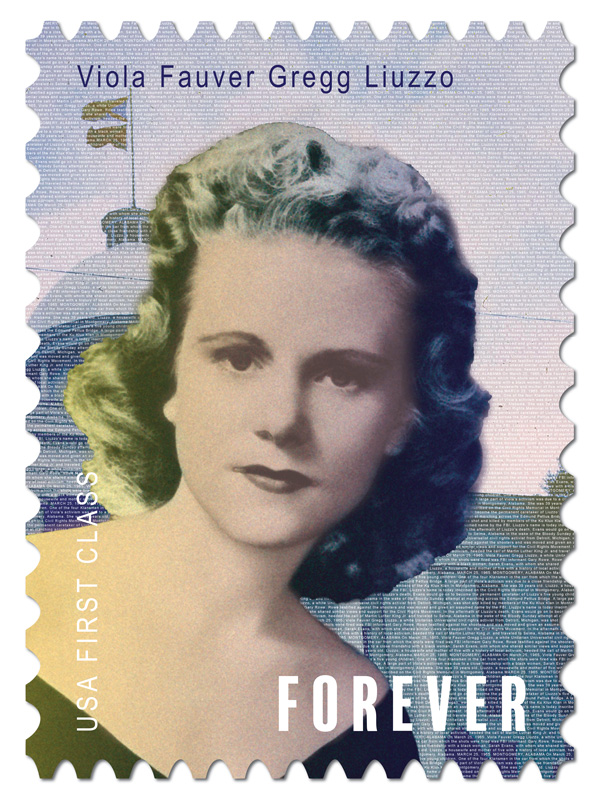

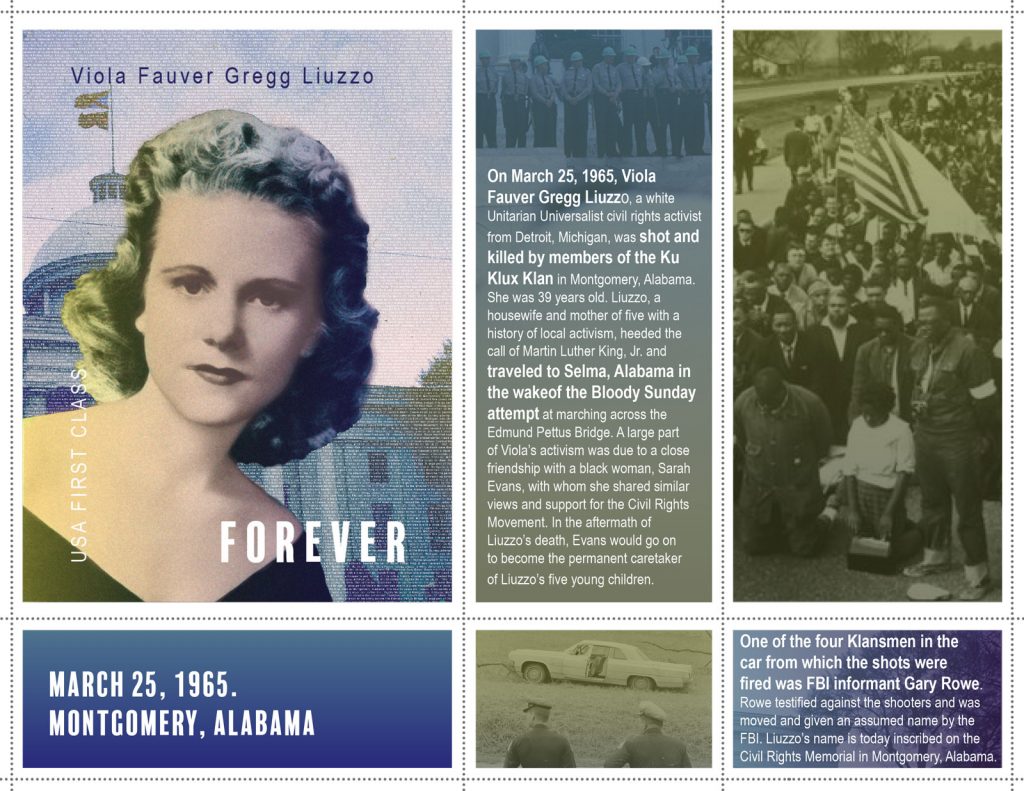

MARCH 25, 1965. MONTGOMERY, ALABAMA

On March 25, 1965, Viola Fauver Gregg Liuzzo, a white Unitarian Universalist civil rights activist from Detroit, Michigan, was shot and killed by members of the Ku Klux Klan in Montgomery, Alabama. She was 39 years old. Liuzzo, a housewife and mother of five with a history of local activism, heeded the call of Martin Luther King Jr. and traveled to Selma, Alabama in the wake of the Bloody Sunday attempt at marching across the Edmund Pettus Bridge. A large part of Viola’s activism was due to a close friendship with a black woman, Sarah Evans, with whom she shared similar views and support for the Civil Rights Movement. In the aftermath of Liuzzo’s death, Evans would go on to become the permanent caretaker of Liuzzo’s five young children. One of the four Klansmen in the car from which the shots were fired was FBI informant Gary Rowe. Rowe testified against the shooters and was moved and given an assumed name by the FBI. Liuzzo’s name is today inscribed on the Civil Rights Memorial in Montgomery, Alabama.

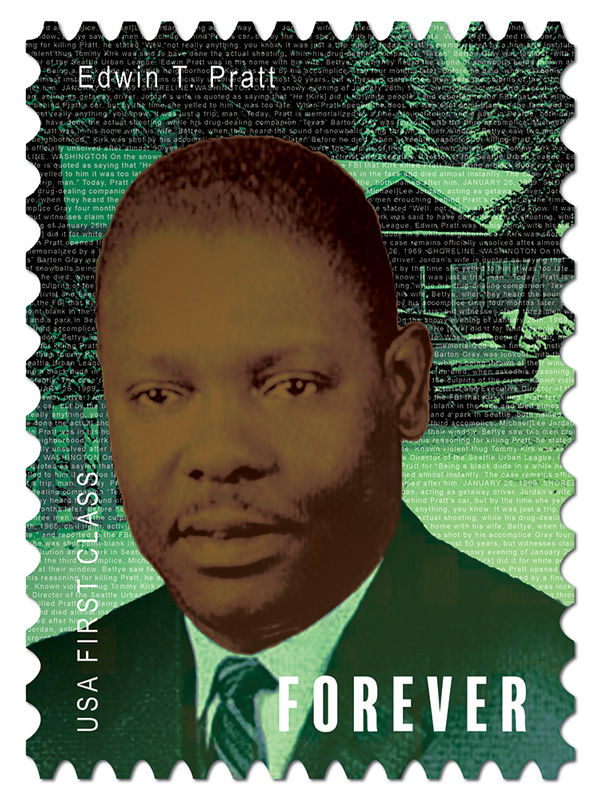

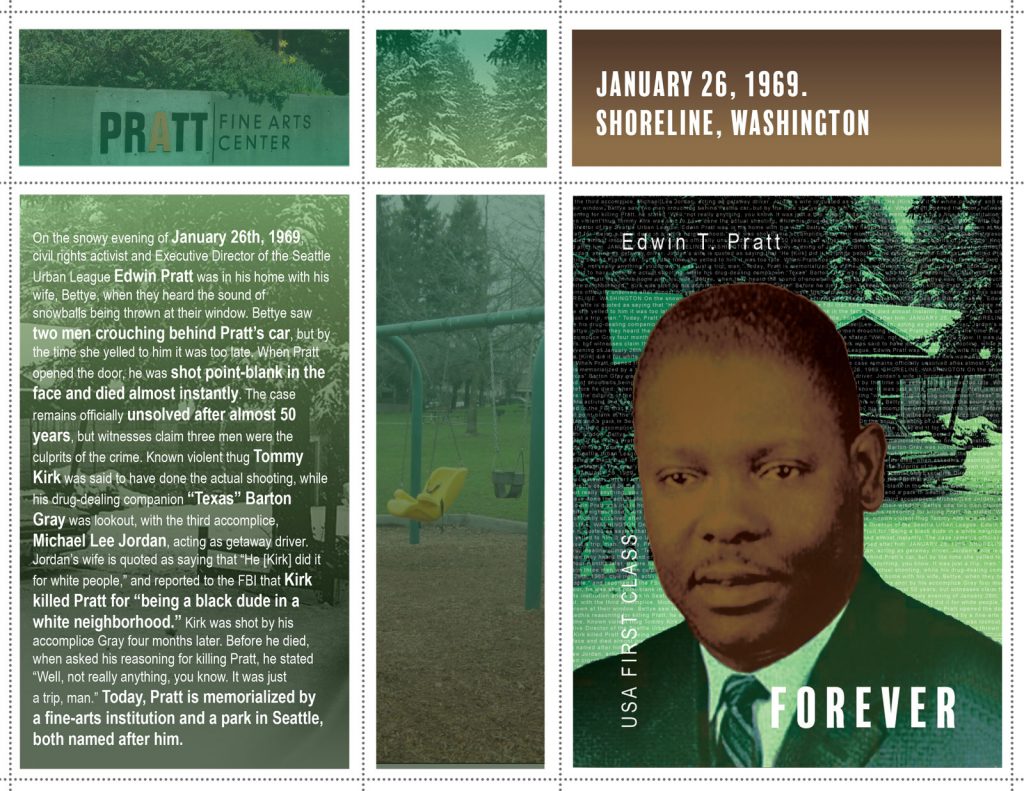

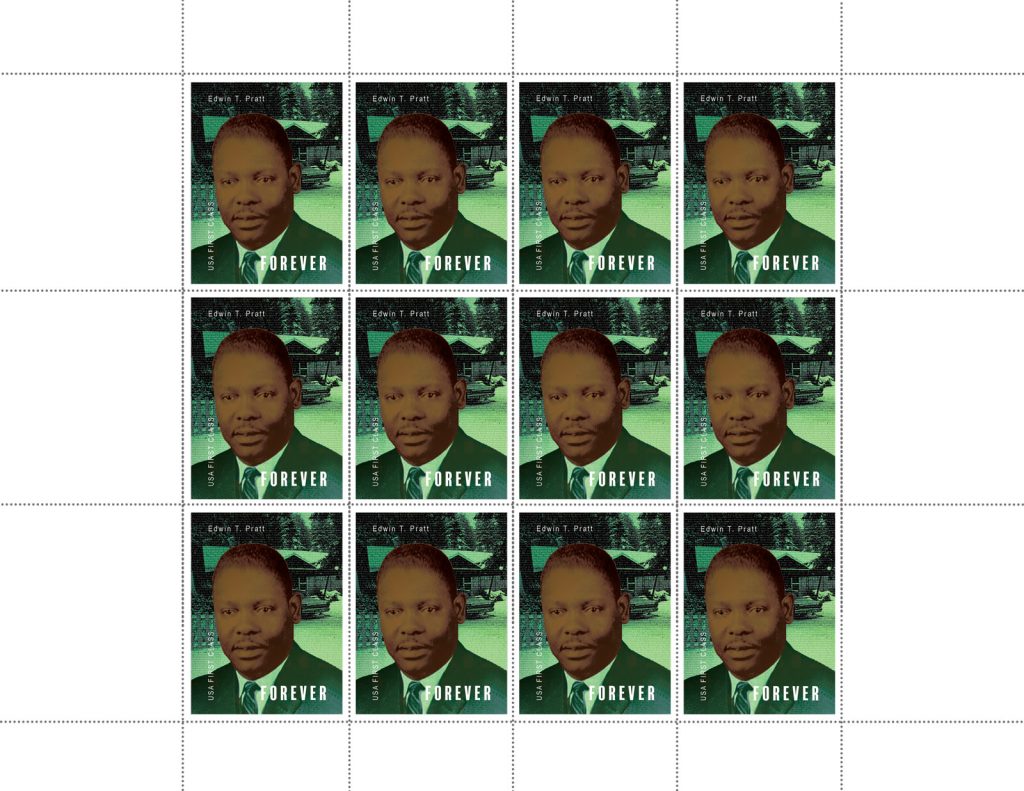

JANUARY 26, 1969. SHORELINE, WASHINGTON

On the snowy evening of January 26th, 1969, civil rights activist and Executive Director of the Seattle Urban League, Edwin Pratt was in his home with his wife, Bettye, when they heard the sound of snowballs being thrown at their window. Bettye saw two men crouching behind Pratt’s car, but by the time she yelled to him it was too late. When Pratt opened the door, he was shot point-blank in the face and died almost instantly. The case remains officially unsolved after almost 50 years, but witnesses claim three men were the culprits of the crime. Known violent thug Tommy Kirk was said to have done the actual shooting, while his drug-dealing companion “Texas” Barton Gray was lookout, with the third accomplice, Michael Lee Jordan, acting as getaway driver. Jordan’s wife is quoted as saying that “He [Kirk] did it for white people,” and reported to the FBI that Kirk killed Pratt for “Being a black dude in a white neighborhood.”

Kirk was shot by his accomplice Gray four months later. Before he died, when asked his reasoning for killing Pratt, he stated “Well, not really anything, you know. It was just a trip, man.”

Today, Pratt is memorialized by a fine-arts institution and a park in Seattle, both named after him.

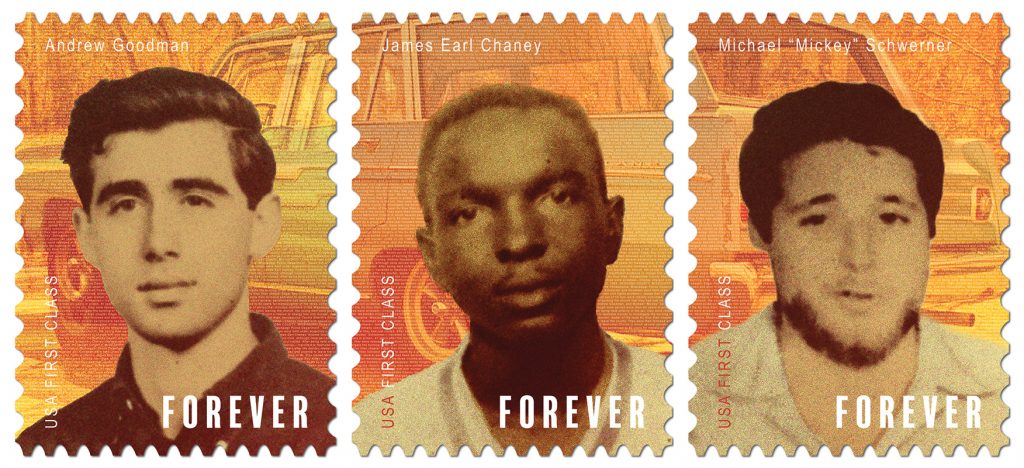

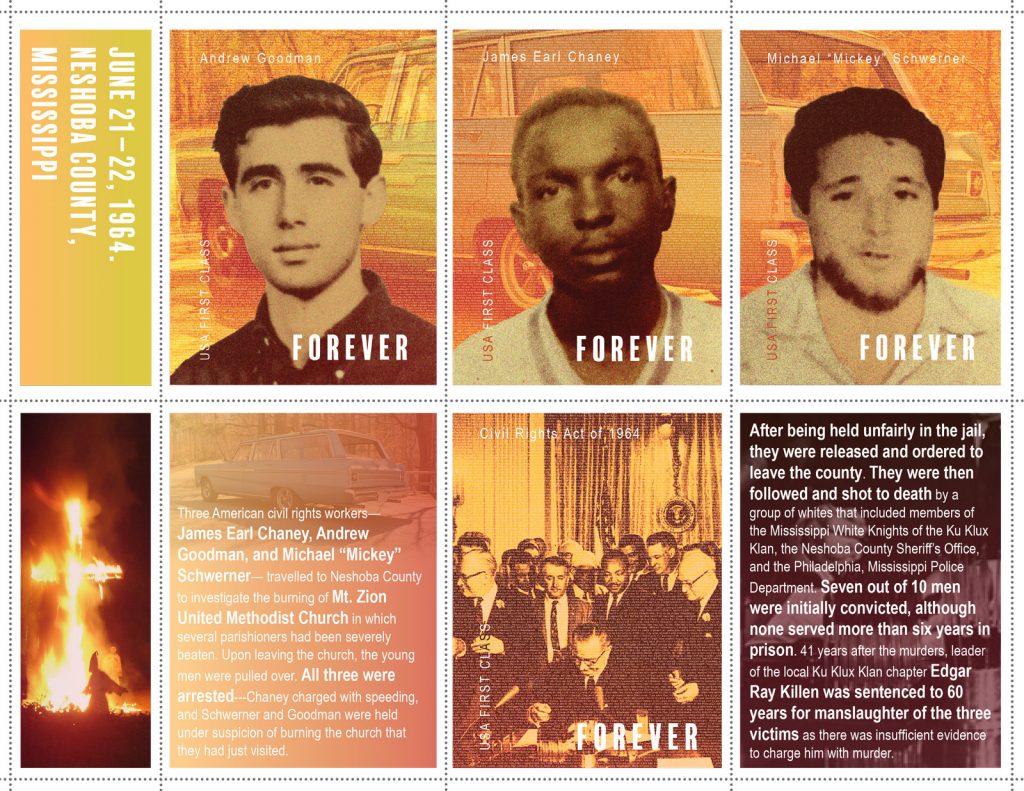

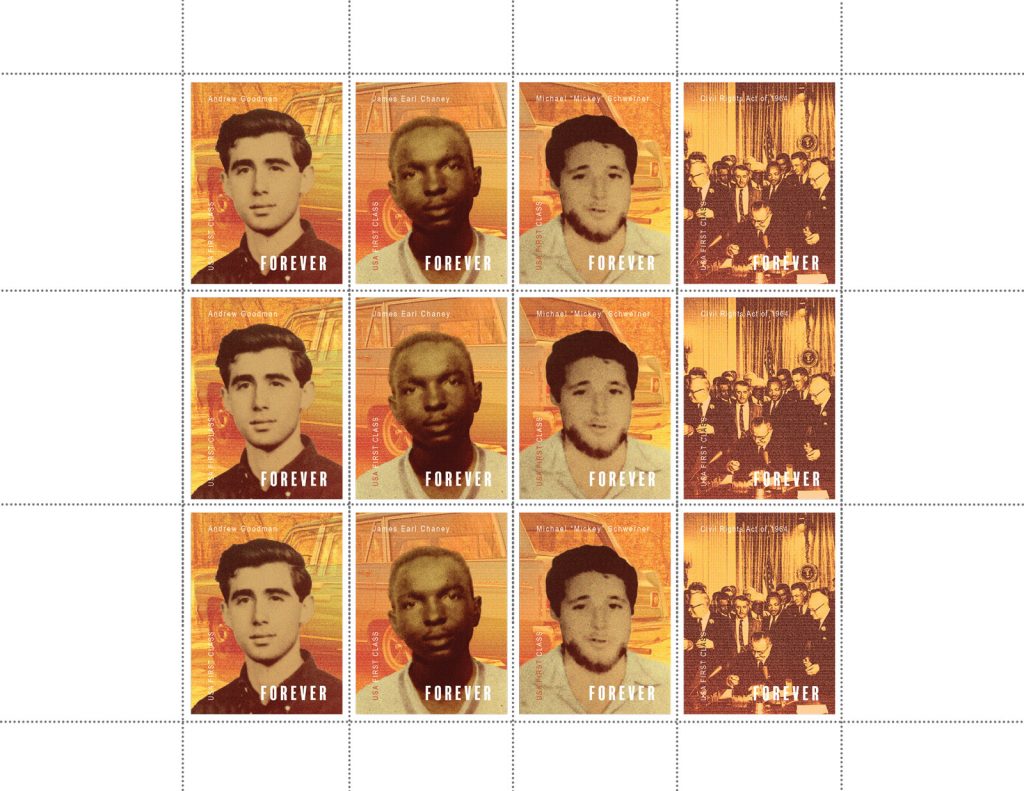

JUNE 21–22, 1964. NESHOBA COUNTY, MISSISSIPPI

Three American civil rights workers— James Earl Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael “Mickey” Schwerner— travelled to Neshoba County to investigate the burning of Mt. Zion United Methodist Church in which several parishioners had been severely beaten. Upon leaving the church, the young men were pulled over. All three were arrested—Chaney charged with speeding, and Schwerner and Goodman were held under suspicion of burning the church that they had just visited. After being held unfairly in the jail, they were released and ordered to leave the county. They were then followed and shot to death by a group of whites that included members of the Mississippi White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, the Neshoba County Sheriff’s Office, and the Philadelphia, Mississippi Police Department. Seven out of 10 men were initially convicted, although none served more than six years in prison. 41 years after the murder, leader of the local Ku Klux Klan chapter Edgar Ray Killen was sentenced to 60 years for manslaughter of the three victims as there was insufficient evidence to charge him with murder.

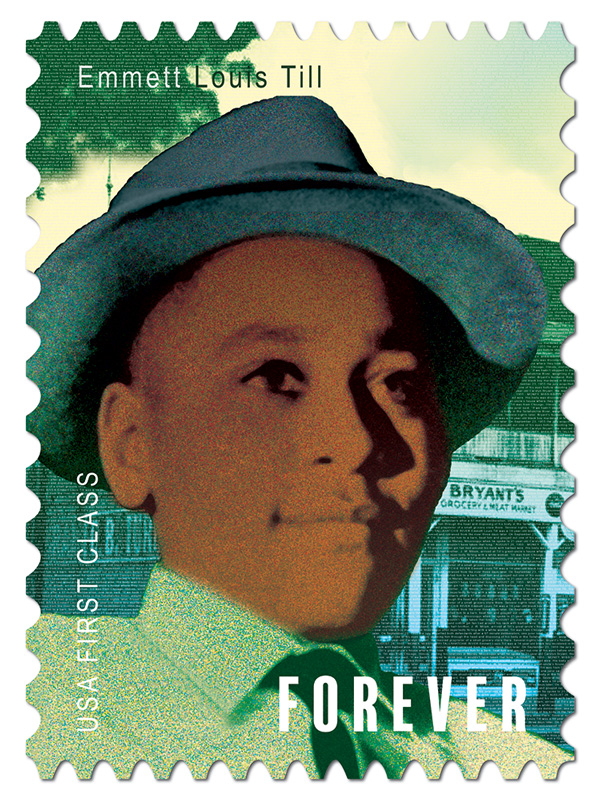

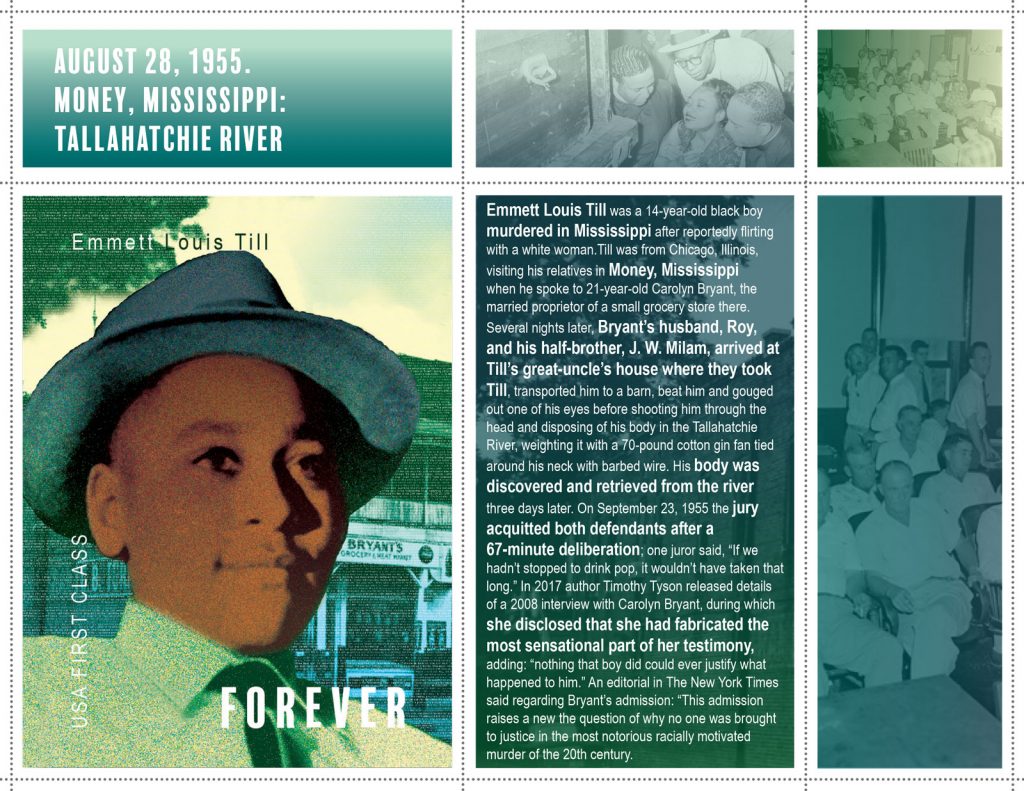

AUGUST 28, 1955. MONEY, MISSISSIPPI: TALLAHATCHIE RIVER

Emmett Louis Till was a 14-year-old black boy murdered in Mississippi after reportedly flirting with a white woman.

Till was from Chicago, Illinois, visiting his relatives in Money, Mississippi when he spoke to 21-year-old Carolyn Bryant, the married proprietor of a small grocery store there. Several nights later, Bryant’s husband, Roy, and his half-brother, J. W. Milam, arrived at Till’s great-uncle’s house where they took Till, transported him to a barn, beat him and gouged out one of his eyes before shooting him through the head and disposing of his body in the Tallahatchie River, weighting it with a 70-pound cotton gin fan tied around his neck with barbed wire. His body was discovered and retrieved from the river three days later.

On September 23, 1955 the jury acquitted both defendants after a 67-minute deliberation; one juror said, “If we hadn’t stopped to drink pop, it wouldn’t have taken that long.”

In 2017 author Timothy Tyson released details of a 2008 interview with Carolyn Bryant, during which she disclosed that she had fabricated the most sensational part of her testimony, adding: “nothing that boy did could ever justify what happened to him.” An editorial in The New York Times said regarding Bryant’s admission: “This admission raises anew the question of why no one was brought to justice in the most notorious racially motivated murder of the 20th century.

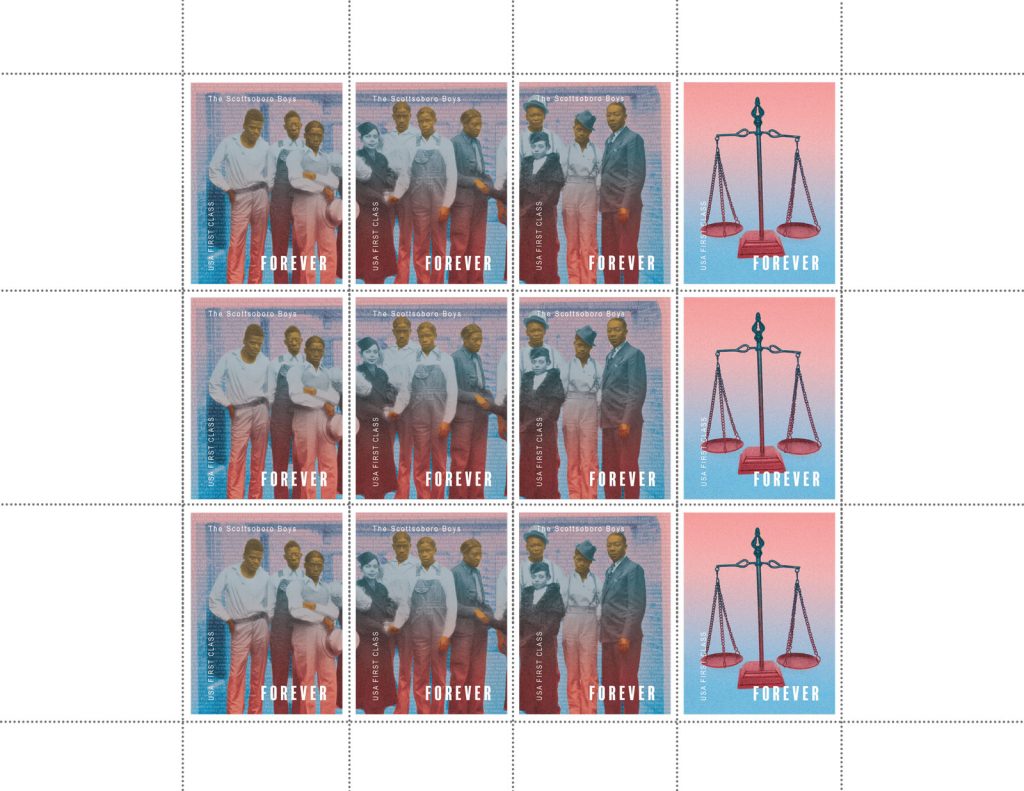

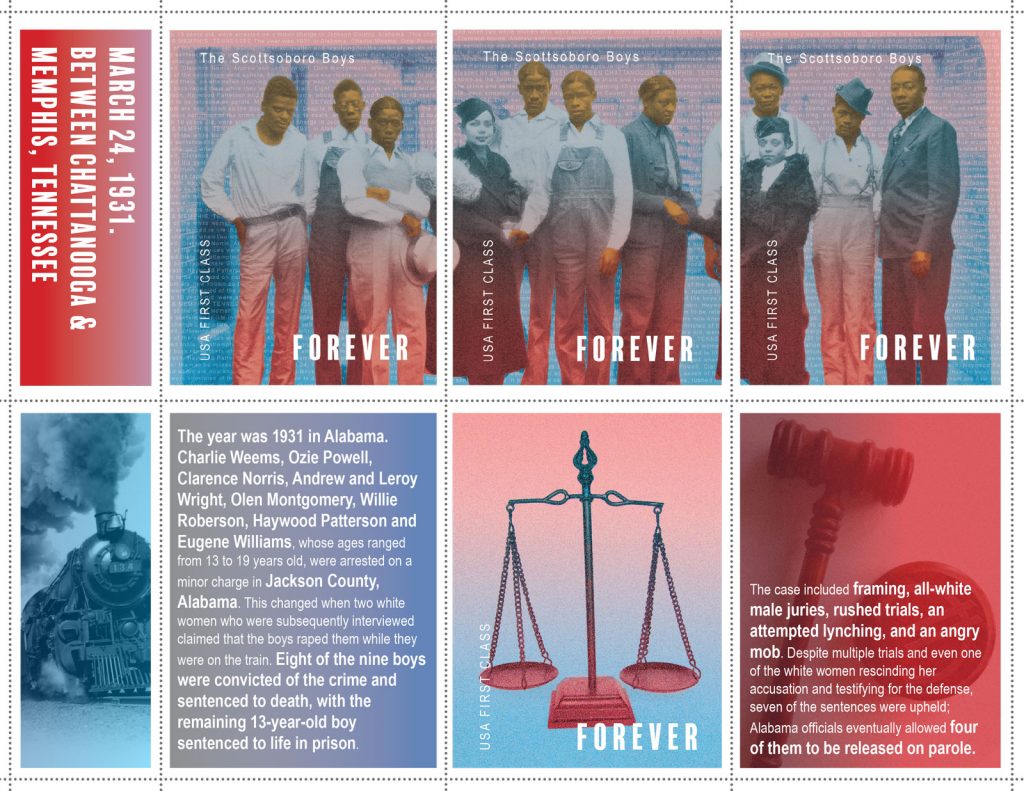

MARCH 24, 1931. BETWEEN CHATTANOOGA & MEMPHIS, TENNESSEE

The year was 1931 in Alabama. Charlie Weems, Ozie Powell, Clarence Norris, Andrew and Leroy Wright, Olen Montgomery, Willie Roberson, Haywood Patterson and Eugene Williams, whose ages ranged from 13 to 19 years old, were arrested on a minor charge in Jackson County, Alabama. This changed when two white women who were subsequently interviewed claimed that the boys raped them while they were on the train. Eight of the nine boys were convicted of the crime and sentenced to death, with the remaining 13 year old boy sentenced to life in prison. The case included framing, all-white male juries, rushed trials, an attempted lynching, and an angry mob. Despite multiple trials and even one of the white women rescinding her accusation and testifying for the defense, seven of the sentences were upheld; Alabama officials eventually allowed four of them to be released on parole.