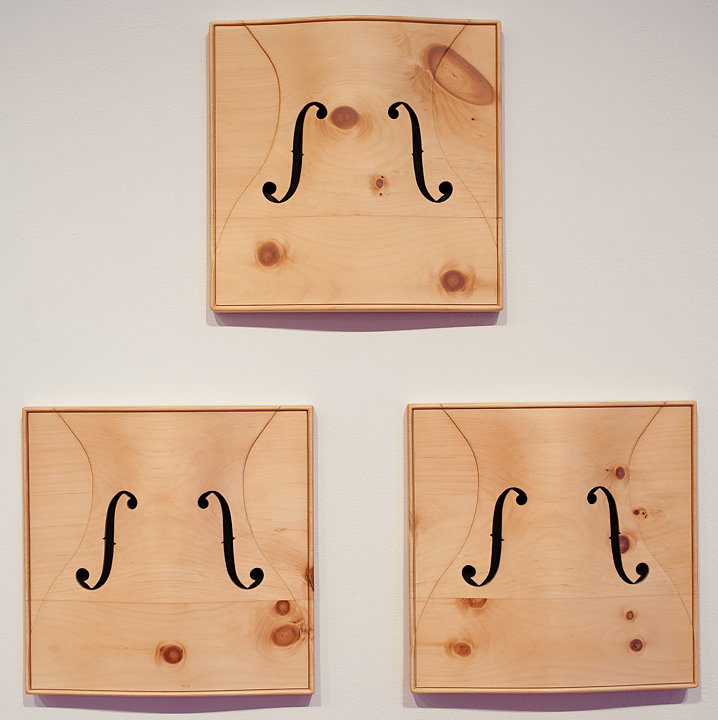

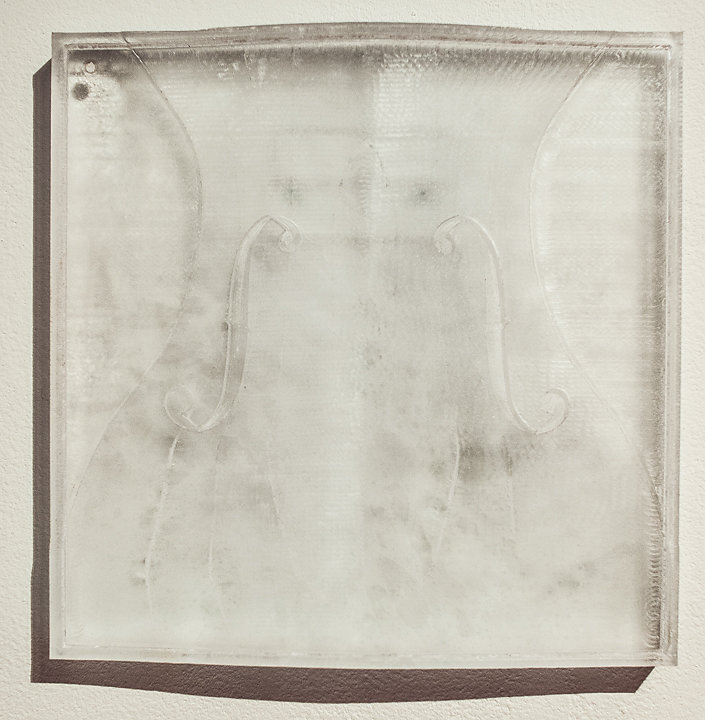

Soundless Series is a group of wood sculptures resembling stringed instrument bodies, and marked with the date and location of death and historical event.

As a musician, Paul Rucker’s primary instrument is the cello—a metaphor for the human body in his artwork.

Addie Mae Collins, Denise McNair, Carole Robertson, and Cynthia Wesley.

In the early morning of Sunday, September 15, 1963, Bobby Frank Cherry, Thomas Blanton, Herman Frank Cash, and Robert Chambliss, members of United Klans of America (a Ku Klux Klan group) planted a box of dynamite with a time delay under the steps of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, near the basement. At about 10:22am, twenty-six children were walking into the basement assembly room to prepare for the sermon entitled “The Love That Forgives,” when the bomb exploded. Four girls, Addie Mae Collins (age 14), Denise McNair (age 11), Carole Robertson (age 14), and Cynthia Wesley (age 14), were killed in the attack, and 22 additional people were injured, one of whom was Addie Mae Collins’ younger sister, Sarah.

A witness identified Robert Chambliss, a member of the Ku Klux Klan, as the man who placed the bomb under the steps of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church. He was arrested but only charged with possessing a box of 122 sticks of dynamite without a permit. On October 8, 1963, Chambliss received a hundred-dollar fine and a six-month jail sentence for having the dynamite. At the time, no federal charges were filed on Chambliss.

The case was unsolved until William Baxley was elected Attorney General of Alabama. He requested the original FBI files on the case and discovered that the organization had accumulated a great deal of evidence against Chambliss that had not been used in the original trial.

In November 1977, the seemingly forgotten case of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church bombing was brought to court, where Chambliss, now aged 73, was tried once again and was found guilty and sentenced to life imprisonment. Chambliss died in an Alabama prison on October 29, 1985.

On May 18, 2000, the FBI announced that the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church bombing had been carried out by the Ku Klux Klan splinter group, the Cahaba Boys. It was claimed that four men, Robert Chambliss, Herman Cash, Thomas Blanton and Bobby Cherry had been responsible for the crime. Cash was dead but Blanton and Cherry were arrested, and both tried and convicted.

Thomas E. Blanton, Jr. was tried in 2001 and found guilty at age 62 of four counts of murder and sentenced to life in prison.

Herman Cash died in 1994 without having been charged. Bobby Frank Cherry, also a former Klansman, was indicted in 2001 along with Blanton. Judge James Garrett of Jefferson County Circuit Court ruled “that Mr. Cherry’s trial would be delayed indefinitely because a court-ordered psychiatric evaluation concluded that he was mentally incompetent.” He was later convicted in 2002, sentenced to life in prison, and died in 2004.

The Groveland Four (or the Groveland Boys) were four young African-American men: Ernest Thomas, Charles Greenlee, Samuel Shepherd and Walter Irvin, who were accused of raping a 17-year-old white woman in Lake County, Florida, USA, in 1948. Thomas was killed as a suspect by a posse after leaving the area; Greenlee, Shepherd and Irvin were beaten while in jail to coerce confessions, but Irvin refused to confess falsely. The three survivors were each convicted at trial by an all-white jury; Greenlee was sentenced to life because he was only 16 at the time of the event; the other two were sentenced to death. A retrial was ordered by the United States Supreme Court after hearing their appeals, led by Thurgood Marshall of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund.

In 1951 Sheriff Willis McCall shot both Shepherd and Irvin in November 1951 while they were in his custody, saying they tried to escape. Shepherd died on the spot, and Irvin told investigators the sheriff shot them in cold blood. At the second trial, Irvin was convicted again and sentenced to death. His sentence was commuted to life by the governor in 1955. Irvin was paroled in 1968; he died in 1970 while visiting Lake County.

Leo Frank

Leo Max Frank (April 17, 1884 – August 17, 1915) was a Jewish-American factory superintendent whose murder trial and extrajudicial hanging in 1915 by a lynch mob planned and led by prominent citizens in Marietta, Georgia, drew attention to questions of antisemitism in the United States.

An engineer and superintendent of the National Pencil Company in Atlanta, Frank was convicted on August 25, 1913, for murdering one of his factory workers, 13-year-old Mary Phagan. She had been strangled on April 26th, and was found dead in the factory cellar the next morning. A state physician conducting the autopsy indicated evidence of sexual violence. Frank was the last person known to have seen her alive, and there were allegations that he had sexually harassed her before. His trial became the focus of powerful class, regional, and political interests. Raised in New York, he was cast as a representative of Yankee capitalism, a rich northern Jew in contrast to the poverty experienced by Phagan and many working-class Southerners of the time. There was jubilation in the streets when Frank was convicted and sentenced to death.

During the height of the summer Frank narrowly survived a prison attack after his throat was slashed. One month later, when he was kidnapped from the penitentiary by a group of 25 armed men who called themselves “Knights of Mary Phagan”. Frank was driven 170 miles from Milledgville to Frey’s Gin and lynched. A crowd gathered after the hanging; one man repeatedly stomped on Frank’s face, while others took photographs, pieces of his nightshirt, and bits of the rope as souvenirs.

In 1982, Alonzo Mann, who had been Frank’s office boy for three weeks at the time of Phagan’s murder, told a journalist for the Tennessean newspaper, nearly 69 years after the trial ended, that he had seen Jim Conley alone shortly after noon in the factory carrying Phagan’s body through the lobby toward the ladder descending to the basement. This contradicted Conley’s testimony that he moved Phagan’s dead body to the basement by the elevator. Mann swore in an affidavit in the 1980s that Conley had threatened to kill him if he reported what he had seen. At the time of the events Mann was aged 14. After telling his family what he had seen, his parents made him swear not to tell anyone else. Mann explained that his statement was made in an effort to die in peace. He passed a lie detector test, and died three years later in March, 1985, at the age of 86.

Frank was posthumously pardoned in 1986 which the Georgia State Board of Pardons and Paroles stated was “in an effort to heal old wounds,” without officially absolving him of the crime.

(Whistles every 67 minutes)

Emmett Louis Till

Emmett Louis Till was an African-American boy who was murdered in Mississippi at the age of 14 after reportedly flirting with a white woman. Till was from Chicago, Illinois, visiting his relatives in Money, Mississippi, in the Mississippi Delta region, when he spoke to 21-year-old Carolyn Bryant, the married proprietor of a small grocery store there. Several nights later, Bryant’s husband Roy and his half-brother J. W. Milam arrived at Till’s great-uncle’s house where they took Till, transported him to a barn, beat him and gouged out one of his eyes, before shooting him through the head and disposing of his body in the Tallahatchie River, weighting it with a 70-pound (32 kg) cotton gin fan tied around his neck with barbed wire. His body was discovered and retrieved from the river three days later.

On September 23, 1955 the jury acquitted both defendants after a 67-minute deliberation; one juror said, “If we hadn’t stopped to drink pop, it wouldn’t have taken that long.”

Trayvon Martin

On the evening of February 26, 2012, George Zimmerman observed Trayvon Martin as he returned to the Twin Lakes housing community after having walked to a nearby convenience store. At the time, Zimmerman was driving through the neighborhood on a personal errand.

At approximately 7:09pm, Zimmerman called the Sanford police non-emergency number to report what he considered a suspicious person in the Twin Lakes community. Zimmerman stated, “We’ve had some break-ins in my neighborhood, and there’s a real suspicious guy.” He described an unknown male “just walking around looking about” in the rain and said, “This guy looks like he is up to no good or he is on drugs or something.” Zimmerman reported that the person had his hand in his waistband and was walking around looking at homes. On the recording, Zimmerman is heard saying, “These assholes, they always get away.”

About two minutes into the call, Zimmerman said, “He’s running.” The dispatcher asked, “He’s running? Which way is he running?” Noises on the tape at this point have been interpreted by some media outlets as the sound of a car door chime, possibly indicating Zimmerman opened his car door. Zimmerman followed Martin, eventually losing sight of him. The dispatcher asked Zimmerman if he was following him. When Zimmerman answered, “yeah”, the dispatcher said, “We don’t need you to do that.” Zimmerman responded, “Okay.” Zimmerman asked that police call him upon their arrival so he could provide his location. Zimmerman ended the call at 7:15pm.

After Zimmerman ended his call with police, a violent encounter took place between Martin and Zimmerman, which ended when Zimmerman fatally shot Martin 70 yards from the rear door of the townhouse where Martin was staying.

A jury later found Zimmerman not guilty.

The Red Summer race riots occurred in more than three dozen cities in the United States during the summer and early autumn of 1919.

Between January 1 and September 14, 1919, white mobs lynched at least forty-three African Americans, with sixteen hanged and others shot; while another eight men were burned at the stake. The states appeared powerless or unwilling to interfere or prosecute such mob murders. The1919 events were among the first in which blacks in number resisted white attacks.

Following the war, rapid demobilization of the military without a plan for absorbing veterans into the job market, and the removal of price controls, led to unemployment and inflation that increased competition for jobs. This, in addition to national media portraying returning black soldiers as Bolshevists, set the stage for the Red Summer Riots.

The NAACP sent a telegram of protest to President Woodrow Wilson (who had segregated federal offices after his election and instituted discriminatory hiring):

“…the shame put upon the country by the mobs, including United States soldiers, sailors, and marines, which have assaulted innocent and unoffending negroes in the national capital. Men in uniform have attacked negroes on the streets and pulled them from streetcars to beat them. Crowds are reported …to have directed attacks against any passing negro….The effect of such riots in the national capital upon race antagonism will be to increase bitterness and danger of outbreaks elsewhere. National Association for the Advancement of Colored People calls upon you as President and Commander in Chief of the Armed Forces of the nation to make statement condemning mob violence and to enforce such military law as situation demands.”

W. E. B. Du Bois, an official of the NAACP and editor of its monthly magazine, published his essay “Returning Soldiers”:

“We return from the slavery of uniform which the world’s madness demanded us to don to the freedom of civil garb. We stand again to look America squarely in the face and call a spade a spade. We sing: This country of ours, despite all its better souls have done and dreamed, is yet a shameful land….

We return.

We return from fighting.

We return fighting.”

Vernon Ferdinand Dahmer, Sr. (March 10, 1908 – January 11, 1966) was an American civil rights leader and president of the Forrest County chapter of the NAACP in Hattiesburg, Mississippi.

He was light-skinned enough to pass as white, but chose to forgo the privileges of living as a white man in Mississippi at that time. In March 1952 Dahmer married Ellie Jewell Davis, a teacher from Rose Hill, Mississippi. The couple had eight children in their family. Dahmer was a member of Shady Grove Baptist Church where he served as a music director and Sunday School teacher. He became the owner of a grocery store, sawmill, planing mill, and 200-acre cotton farm.

On the night of January 10, 1966, the Dahmer home was firebombed. As Ellie and her children escaped the inferno, gunshots were fired from the streets and Vernon returned fire from inside the house. He was severely burned from the waist up before he could escape and died the next day. The Dahmer home, grocery store, and car were destroyed in the fire.

Authorities indicted fourteen men, most with Ku Klux Klan connections. Thirteen were brought to trial, eight on charges of arson and murder. Four were convicted and one Billie Roy Pitts entered a guilty plea and turned state’s evidence. However three out four of those convicted were pardoned within four years. In addition, eleven of the defendants were tried on federal charges of conspiracy to intimidate Dahmer because of his civil rights activities. Former Klan Imperial Wizard Sam Bowers, who was believed to have ordered the attack, was tried four times, but each ended in a mistrial.

Based on new evidence, the state of Mississippi reopened the case, and in1998 tried Bowers for the murder of Dahmer and assault on his family. The jury convicted Bowers and the judge sentenced him to life in prison. He died in Mississippi State Penitentiary on November 5, 2006.

Eric Garner

On July 17, 2014, Eric Garner died in Staten Island, New York, after a police officer put him in a chokehold. The New York City Medical Examiner’s Office concluded that Garner died partly as a result of the chokehold. New York City Police Department (NYPD) policy prohibits the use of chokeholds, and law enforcement personnel contend that it was a headlock and that no choking took place.

After Garner expressed to the police that he was tired of being harassed and that he was not selling cigarettes, officers moved to arrest Garner on suspicion of selling “loosies” (single cigarettes) from packs without tax stamps. When officer Daniel Pantaleo took Garner’s wrist behind his back, Garner swatted his arms away. Pantaleo then put his arm around Garner’s neck and pulled him backwards and down onto the ground. After Pantaleo removed his arm from Garner’s neck, he pushed Garner’s head into the ground while four officers moved to restrain Garner, who repeated “I can’t breathe” eleven times while lying facedown on the sidewalk. After Garner lost consciousness, officers turned him onto his side to ease his breathing. Garner remained lying on the sidewalk for seven minutes while the officers waited for an ambulance to arrive. The officers and EMTs did not perform CPR on Garner at the scene; according to a spokesman for the Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association of the City of New York, this was because they believed that Garner was breathing and that it would be improper to perform CPR on someone who was still breathing. He was pronounced dead on arrival at the hospital approximately one hour later.

Medical examiners concluded that Garner was killed by “compression of neck (choke hold), compression of chest and prone positioning during physical restraint by police”, though no damage to his windpipe or neck bones was found. The medical examiner ruled Garner’s death a homicide, indicating that his death was caused by the intentional actions of another person or persons; however, the designation of homicide by itself means neither that the death itself was intentional nor that a crime was committed.

On December 3, 2014, a grand jury decided not to indict Pantaleo. The event stirred public protests and rallies with charges of police brutality. As of December 28, 2014, at least 50 demonstrations had been held nationwide specifically for Garner while hundreds of demonstrations against general police brutality counted Garner as a focal point. The Justice Department announced an independent federal investigation.

James Byrd, Jr.

James Byrd, Jr. was an African-American who was murdered by three men, of whom at least two were white supremacists, in Jasper, Texas, on June 7, 1998. Shawn Berry, Lawrence Russell Brewer, and John King dragged Byrd for three miles behind a pick-up truck along an asphalt road.

On June 7, 1998, Byrd, age 49, accepted a ride from Shawn Berry (age 24), Lawrence Russell Brewer (age 31) and John King (age 23). Berry, who was driving, was acquainted with Byrd from around town. Instead of taking Byrd home, the three men took Byrd to a remote county road out of town, beat him severely, urinated on him and chained him by his ankles to their pickup truck before dragging him for three miles. Brewer later claimed that Byrd’s throat had been slashed by Berry before he was dragged. However, forensic evidence suggests that Byrd had been attempting to keep his head up while being dragged, and an autopsy suggested that Byrd was alive during much of the dragging. Byrd died after his right arm and head were severed after his body hit a culvert. The murderers drove on for another mile before dumping his torso in front of an African-American cemetery in Jasper. Byrd’s brain and skull were found intact, further suggesting he maintained consciousness while being dragged.

Lawrence Russell Brewer was executed by lethal injection for this crime by the state of Texas on September 21, 2011. King remains on Texas’ death row while appeals are pending, while Berry was sentenced to life imprisonment.

Byrd’s lynching-by-dragging gave impetus to passage of a Texas hate crimes law. It later led to the federal Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act, commonly known as the Matthew Shepard Act, which passed on October 22, 2009, and which President Barack Obama signed into law on October 28, 2009.

JACKSON, MISSISSIPPI

Medgar Evers was a black civil rights activist from Mississippi involved in efforts to overturn segregation at the University of Mississippi. After returning from overseas military service in World War II and completing his secondary education, he became active in the civil rights movement. In late 1954, Evers was named the NAACP’s first field secretary for Mississippi. In this position, he helped set up new local chapters, along with leading boycotts, organizing voter registration, and investigating crimes against black people. Evers was outspoken on Emmett Till’s case, as well as on unfair convictions against his fellow members in the civil rights movement. His achievements made him a target of multiple racist groups, which entailed a firebombing of his house during May in 1963. A month later, Medgar was shot in the back in his own driveway. The prime suspect was Byron De La Beckwith, a white segregationist, Klansman, and founder of Mississippi’s White Citizens Council. Although he initially walked free, decades later evidence came to light that the all-white jury had been tampered with by segregationist committees who aided his lawyers. Several individuals also testified that Beckwith had bragged to them about the murder. 31 years after Ever’s passing, Beckwith was finally convicted and sentenced to life in prison for first degree murder in 1994.

Three American civil rights’ workers, James Earl Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael “Mickey” Schwerner, were shot at close range on the night of June 21–22, 1964 by members of the Mississippi White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, the Neshoba County Sheriff’s Office and the Philadelphia, Mississippi Police Department. The three had been working on the “Freedom Summer” campaign, attempting to register African Americans to vote.

The White Knights were a splinter group more belligerent than other KKK groups. They would soon command a following of nearly 10,000 white Mississippians, preparing for a conflict not seen since the Civil War, in defiance of new federal authority regarding racial integration.

March 24, 1931

The Scottsboro Boys

The Scottsboro Boys were nine black teenagers accused of rape in Alabama in 1931. The landmark set of legal cases from this incident dealt with racism and the right to a fair trial. The case included a frameup, an all-white jury, rushed trials, an attempted lynching, and an angry mob; it is frequently given as an example of an overall miscarriage of justice.

On March 24, 1931, on the Southern Railway line between Chattanooga and Memphis, Tennessee, nine black youths were “hoboing” on a freight train with several white males and two white women.

A fight began between the white and black groups, and the whites were kicked off the train. A posse in Paint Rock, Alabama, was given orders to “capture every Negro on the train”. The black teenagers were arrested for assault. The posse also encountered two white women, Ruby Bates and Victoria Price, who said that they had been raped by the black teenagers.

In the Jim Crow South, lynching of black males accused of raping or murdering whites was common and word quickly spread of the arrest and rape story. Soon a lynch mob gathered at the jail in Scottsboro, demanding the youths be surrendered. The National Guard was called in to protect the jail.

The cases were appealed and transferred back and forth between the state court and United States Supreme Courts several times. Eventually both women who had made accusations of rape were proven to have lied. On November 21, 2013, the Alabama Board of Pardons and Paroles granted posthumous pardons to Weems, Wright and Patterson, the only Scottsboro Boys who had neither had their convictions overturned nor received a pardon.

Viola Fauver Gregg Liuzzo

On March 25, 1965 Viola Fauver Gregg Liuzzo, a Unitarian Universalist civil rights activist from Michigan, was shot and killed by members of the Ku Klux Klan in Montgomery, Alabama. She was 39 years old. Liuzzo, then a housewife and mother of 5 with a history of local activism, heeded the call of Martin Luther King Jr. and traveled from Detroit, Michigan to Selma, Alabama in the wake of the Bloody Sunday attempt at marching across the Edmund Pettus Bridge. Liuzzo participated in the successful Selma to Montgomery marches and helped with coordination and logistics.

One of the four Klansmen in the car from which the shots were fired was FBI informant Gary Rowe. Rowe testified against the shooters and was moved and given an assumed name by the FBI.

Liuzzo’s name is today inscribed on the Civil Rights Memorial in Montgomery, Alabama.

Lynching of Jesse Washington

Jesse Washington, a teenage African-American farmhand, was lynched in Waco, Texas, on May 15, 1916, in what became a well-known example of racially motivated lynching. Washington was accused of raping and murdering Lucy Fryer, the wife of his white employer in rural Robinson, Texas. There were no eyewitnesses to the crime, but during his interrogation by the McLennan County sheriff he signed a confession and described the location of the murder weapon.

Washington was tried for murder in Waco, in a courtroom filled with furious locals. He entered a guilty plea, was quickly sentenced to death, dragged out of the court by observers and lynched in front of Waco’s city hall. Over 10,000 spectators, including city officials and police, gathered to watch the attack. There was a celebratory atmosphere at the event, and many children attended during their lunch hour. Members of the mob castrated Washington, cut off his fingers, and hung him over a bonfire. He was repeatedly lowered and raised over the fire for about two hours. After the fire was extinguished, his charred torso was dragged through the town and parts of his body were sold as souvenirs. A professional photographer took pictures as the event unfolded, providing rare imagery of a lynching in progress. The pictures were printed and sold as postcards in Waco.

The lynching drew a large crowd, including the mayor and the chief of police, although lynching was illegal in Texas. Sheriff Fleming told his deputies not to stop the lynching, and no one was arrested after the event. The Sherriff’s actions may have been motivated by a desire to harshly deal with crime to help his candidacy for re-election that year. Mayor John Dollins may have also encouraged the mob owing to the belief that a lynching would be politically beneficial. The crowd numbered 15,000 at its peak.

As the lynching occurred at midday, children from local schools walked downtown to observe, some climbing into trees for a better view. Many parents approved of their children’s attendance, hoping that the lynching would reinforce a belief in white supremacy. Some Texans saw participation in a lynching as a rite of passage for young men.

Although it was supported by many Waco residents, the lynching was condemned by newspapers around the United States. Historians have noted that Washington’s death helped alter the way that lynching was viewed; the publicity it received curbed public support for the practice, which became viewed as barbarism rather than as an acceptable form of justice.

Emmanuel K Love’s Sermon

On November 5, 1893, a prominent Baptist preacher gave a sermon concerning lynching, rape, and mob violence against African Americans in the South. In his sermon, Rev. E. K. Love of the First African Baptist Church in Savannah, Georgia advocated equality for all people, black and white. Fifteen hundred people attended the evening church service to hear the sermon given by Love. Love noted “the well-known fact that like begets like”. and that the outrageous acts of lynching would not stop any time soon. His plea was that “The sensible Negroes and conservative whites should unite and frown down these outrages. This can best be done by conservative talk, fair reasoning, confidence and patriotic co-operation.”

By Paul Laurence Dunbar

Pray why are you so bare, so bare,

Oh, bough of the old oak-tree;

And why, when I go through the shade you throw,

Runs a shudder over me?

My leaves were green as the best, I trow,

And sap ran free in my veins,

But I say in the moonlight dim and weird

A guiltless victim’s pains.

I bent me down to hear his sigh;

I shook with his gurgling moan,

And I trembled sore when they rode away,

And left him here alone.

They’d charged him with the old, old crime,

And set him fast in jail:

Oh, why does the dog howl all night long,

And why does the night wind wail?

He prayed his prayer and he swore his oath,

And he raised his hand to the sky;

But the beat of hoofs smote on his ear,

And the steady tread drew nigh.

Who is it rides by night, by night,

Over the moonlit road?

And what is the spur that keeps the pace,

What is the galling goad?

And now they beat at the prison door,

“Ho, keeper, do not stay!

We are friends of him whom you hold within,

And we fain would take him away

“From those who ride fast on our heels

With mind to do him wrong;

They have no care for his innocence,

And the rope they bear is long.”

They have fooled the jailer with lying words,

They have fooled the man with lies;

The bolts unbar, the locks are drawn,

And the great door open flies.

Now they have taken him from the jail,

And hard and fast they ride,

And the leader laughs low down in his throat,

As they halt my trunk beside.

Oh, the judge, he wore a mask of black,

And the doctor one of white,

And the minister, with his oldest son,

Was curiously bedight.

Oh, foolish man, why weep you now?

‘Tis but a little space,

And the time will come when these shall dread

The mem’ry of your face.

I feel the rope against my bark,

And the weight of him in my grain,

I feel in the throe of his final woe

The touch of my own last pain.

And never more shall leaves come forth

On the bough that bears the ban;

I am burned with dread, I am dried and dead,

From the curse of a guiltless man.

And ever the judge rides by, rides by,

And goes to hunt the deer,

And ever another rides his soul

In the guise of a mortal fear.

And ever the man he rides me hard,

And never a night stays he;

For I feel his curse as a haunted bough,

On the trunk of a haunted tree.